%%{init: { 'theme': 'base',

'gitGraph': { 'showCommitLabel': false, 'mainBranchOrder': 2, 'parallelCommits': true}

} }%%

gitGraph

commit

commit

branch feature order: 1

commit

commit

checkout main

commit

branch bugfix order: 3

commit

commit

commit

checkout feature

commit

checkout main

merge feature

merge bugfix

commit

Introduction to git and GitHub

ICCS Summer School 2025

2025-07-07

Course material

Slides: https://cambridge-iccs.github.io/Summer-school-Intro-Git

Repo: https://github.com/Cambridge-ICCS/Summer-school-Intro-Git

Warning

We assume you have gone through the preparation

Learning Outcomes

- Be familiar with the building blocks of

git: repositories, commits and branches - Get started with using

gitlocally on your own projects - Get started with collaborating on code projects using GitHub

- Gain an appreciation for how useful Version Control is

Motivation

- Relatable experience when writing your software/documents?

Version Control

Tools like Git and Github exist as solutions to the problem of how to save, share, and collaborate in a structured and safe way.

Useful whether you are working alone or in a team!

What are Version Control Systems (VCSs)?

- Tools to track changes to code

- Maintain a history of changes as a series of snapshots

- Allow to go back in time to a previous state

- Facilitate collaboration

- Require very little overhead for a huge benefit

Why Git?

- De facto standard for VC in the open source community

- Git is open source itself!

- Has a rich ecosystem around

- Distributed VC approach (vs centralized)

- Supports non-linear development (branching)

- Gives fine-grained control

- High performance/Scalable

Github: Hosting and collaboration

- Code hosting platform

- Most widely used to host open source software

- Eases the development with tools

- Pull Requests (PRs)

- Issues and Discussions

- More advance features like Continuous Integration, Automated Testing

In today’s course we will practice how to:

- create a local git repository

- create a git commit in your repository

- create a git branch in your repository

- fork a remote repository and check it out on your local machine

- put in a pr to have our changes merged back to the remote repo

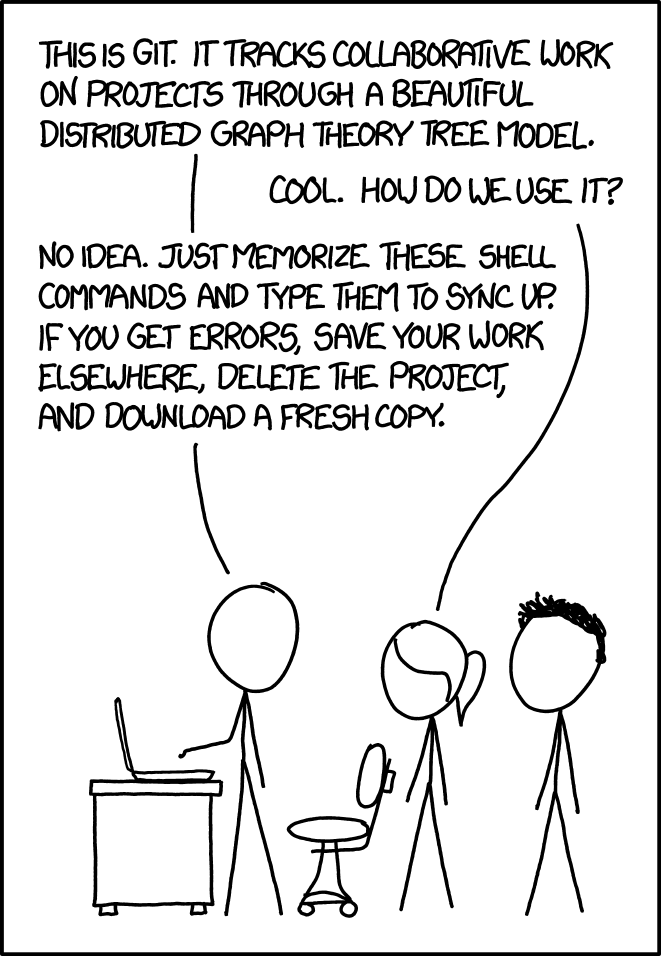

git by xkcd used under cc by-nc 2.5

What is a Git repository?

- A place where you can store your code, your files, and each file’s revision history.

- Contains a

.gitfolder at the root which does all the git magic behind the scenes.

Creating a git repository

- Navigate to a folder you want to work in, and create a new folder to contain your repository:

Then initialise the folder

.git

A hidden .git folder has been created in your folder. This contains everything Git needs to work.

What is a Git commit?

- You can think of a commit as a snapshot of your work at a particular time

- You can navigate between commits easily with git

- This allows you to switch easily between different versions of your work

- When you commit, rather than saving all the files in a project every time, git is efficient and only stores the files which have been changed between the previous commit and your current one

- The commit also stores a reference to its parent commit

Committing is a three part process:

- Modify: change the file in your working tree, i.e., go in and edit the file as usual

- Stage: Tell git that you would like this file to be included in your next commit

- Commit: Tell git to take a snapshot of the files you staged

At each step in the process, the file is stored in a different area:

Git States

git has four main states that your files can be in:

- Untracked: You’ve created a new file and not told git to keep track of it.

- Modified: You’ve changed a file that git already has a record of, but have not told git to include these changes in your next commit. We say these files are in the working tree.

- Staged: You’ve told git to include the file next time you do a commit. We say these files are in the staging area.

- Committed: The file is saved in it’s present state in the most recent commit.

Create an untracked file:

Create an untracked file:

git status

$ git status

On branch main

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

new.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)git status

Highlights your working branch -> main

Reports commit status -> none yet

Highlights untracked files -> new.txt

Proposes adding these to git with git add

Add the untracked file to the staging area:

git add

$ git status

On branch main

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: new.txtgit add

Moves file(s) into “Staging area” ready for commit

Committing your changes:

Committing your changes:

Commit your file to the local git repo

git commit: tells git you want to commit-m "Commit message": adds a human-readable description to thelogof this commit. This is important as it tells you and others what the commit intent is.

Writing meaningful commit message

There are many conventions and good practices to write good commit messages. Based on scope of the project and other factors particular conventions are chosen.

Commit the staged file

git log

$ git log

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Jane Doe <jmd123@cam.ac.uk>

Date: Monday July 7 09:51:46 2025 -0400

Create new.txtgit log

Displays commits in reverse chronological order.

Includes full identifier, author and date

git log --graphshows the dependencies of commits in graph view- especially useful in non-linear development

What is a Git branch?

- A branch is a pointer to a commit, and updates as new commits are made.

- The work done so far has been on the

mainbranch. - Using multiple branches enable collaborative work in parallel without interfering with the changes of others.

![]()

Creating a git branch:

Creating a git branch and checking it out

- Create a new branch using

git branch my-new-branch - Switch to the branch using

git switch my-new-branch - Or, more conveniently, we can combine these actions into one:

- Make a change in your new branch by editing new.txt and committing the changes.

Note

Older versions of git may need to use checkout (-b) instead of switch (-c)

Switching and merging branches

- Return to the main branch:

- Open the new.txt file, what’s inside?

- Now merge the new branch into main:

Note

You can use git switch - as a shortcut for returning to the previous branch.

Why and when to use branches?

Feature branching

- Enables working on multiple tasks concurrently.

- Keeps work-in-progress code out of the main branch.

- Can regularly commit smaller changes without worry.

Tip

Keep branches short-lived. Long branches with large changes become harder and harder to merge.

Ways of working with a remote repository

A remote repository is one stored in the cloud. We will be using GitHub to do this today.

There are two different ways to copy a remote repository so that you can work on it locally:

clone: This makes a copy locally which is linked to the remote version. Your local branches can be synced to branches in the original.

fork: This makes another separate version of the repo remotely that you own. Once you have forked a repo remotely, you can then clone it to your local machine. You can still contribute to the original repository through a pull request.

To clone or to fork?

Use a fork when:

- The owner of the repo is not someone you are actively collaborating with

- You want to take the development of the code in a different direction from the original owner of the repo

- You want full ownership over your version of the codebase

- You want complete control over other’s contributions to the codebase

- You do not want the main branch to receive updates from those editing the original repo

- Or you do not have permission to push branches directly to the original repo

Use a clone when:

- You are collaborating directly and actively with the owner of the repo (e.g. it is your research team, or you)

OR all of the following is true:

- It is owned by someone else and you are happy not to have ownership of the codebase

- You have permission to push branches up to the repo

- You want easy access to the latest changes made by others to the central repository

- You want the main branch in the repo to be updated and edited by others working on the project

Working with remote repositories

Collaborative git with GitHub

Warning

You must have already created a GitHub account before you can do these exercises

Example repository:

https://github.com/Cambridge-ICCS/Summer-School-Intro-Git-Practice

Forking (demo only, not necessary for this exercise)

Forking

At this point, the forked repo only exists in GitHub. To work on it locally it needs to be copied (“cloned”) to your local computer.

Cloning from GitHub

Warning

Clone repo to a new working folder.

Do not clone into an existing local git repo.

Cloning from GitHub

- Create a new branch with a unique name.

- Choose/create a file to edit, and then

commit.

- Next

pushthe changes up to the remote repo.

- The first time you do this on a new branch, you will need to set up a remote one to track it:

git push --set-upstream origin your-branch-name

- For any commits after that on the branch you can use

git pushon its own when you are on the branch you want to push.

Pull requests

The final step is to put in a pull request (PR) to the remote repository.

A pull request is how we signal to the repo owner that we want to merge in our changes.

Depending on the code and the repo, you may not be able to merge directly.

-> Branches can be set up so that you can only merge after a review by one or more developers who may suggest/require edits to you code.

-> Additionally, you can set up Continuous Integration so that the code has to pass tests before it can be merged.

Hopefully you now…

- …are familiar with the building blocks of git: repositories, commits and branches

- …able to use git locally on your own projects

- …know how to get started with collaborating on code projects using GitHub

- …can continue from here and learn more about version control as needed

Final thoughts?

Anything you’d like to revisit or build on from today?

Please come and visit us in a study room session this week.

Book a Code Clinic session anytime during the year:

https://iccs.cam.ac.uk/resources-vesri-members/climate-code-clinic

This course and the intermediate git course will also be made available on YouTube.

Additional material

This is a nice visual resource for learning git:

https://learngitbranching.js.org/

Git documentation:

https://git-scm.com/docs

GUIs for git:

https://git-scm.com/downloads/guis

More git courses:

https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/

https://www.w3schools.com/git/

ICCS Summer School 25